SKIING HISTORY

Editor Seth Masia

Managing Editor Greg Ditrinco

Consulting Editor Cindy Hirschfeld

Art Director Edna Baker

Editorial Board

Seth Masia, Chairman

John Allen, Andy Bigford, John Caldwell, Jeremy Davis, Kirby Gilbert, Paul Hooge, Jeff Leich, Bob Soden, Ingrid Wicken

Founding Editors

Morten Lund, Glenn Parkinson

To preserve skiing history and to increase awareness of the sport’s heritage

ISHA Founder

Mason Beekley, 1927–2001

ISHA Board of Directors

Rick Moulton, Chairman

Seth Masia, President

Wini Jones, Vice President

Jeff Blumenfeld, Vice President

John McMurtry, Vice President

Bob Soden (Canada), Treasurer

Richard Allen, Skip Beitzel, Michael Calderone, Dick Cutler, Wendolyn Holland, Ken Hugessen (Canada), David Ingemie, Joe Jay Jalbert, Henri Rivers, Charles Sanders, Einar Sunde, Christof Thöny (Austria), Ivan Wagner (Switzerland)

Presidential Circle

Christin Cooper, Billy Kidd, Jean-Claude Killy, Bode Miller, Doug Pfeiffer, Penny Pitou, Nancy Greene Raine

Executive Director

Janet White

janet@skiinghistory.org

Membership Services

Fawn Montanye

(802) 367-3408

fawn@skiinghistory.org

Corporate Sponsorships

Peter Kirkpatrick

(541) 944-3095

peterk10950@gmail.com

Bimonthly journal and official publication of the International Skiing History Association (ISHA)

Partners: U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame | Canadian Ski Museum and Hall of Fame

Alf Engen Ski Museum | North American Snowsports Journalists Association | Swiss Academic Ski Club

Skiing History (USPS No. 16-201, ISSN: 23293659) is published bimonthly by the International Skiing History Association, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255.

Periodicals postage paid at Manchester Center, VT and at additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send address changes to ISHA, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255

ISHA is a 501(c)(3) public charity. EIN: 06-1347398

Written permission from the editor is required to reproduce, in any manner, the contents of Skiing History, either in full or in part.

Where are they now? Marco Tonazzi, Versatile Italian

The Vail-based entrepreneur revisits his World Cup and pro racing careers.

World Cup and pro ski racer Mark Taché has known Marco Tonazzi for 44 years. Nothing surprises him about the Italian’s achievements. “Nothing at all,” says Taché.

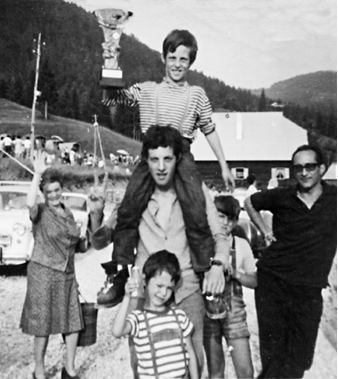

(Photo above: Tonazzi winning the 1985 Italian slalom championship)

Not that Tonazzi runs six businesses in Colorado and Italy with neither a business nor college degree. Not that Tonazzi was the 1990 World Pro Ski Tour Rookie of the Year without ever having made an Olympic appearance. Not that Tonazzi, a slalom specialist, made a World Cup podium in giant slalom—at Adelboden, Switzerland, the crown jewel of GS racing—marking the first one-two finish for the Italian men’s team in 10 years. Not that Tonazzi, who wasn’t even a downhiller, finished the 24 Hours of Aspen race (alone) after 11 knee surgeries.

Surprising or not, Tonazzi’s life has taken an incredible trajectory through three decades of pro and Italian ski racing history, overlapping with legends Gustavo Thöni, Alberto Tomba and more.

The story begins in Udine, a city of 100,000 in the northeast corner of Italy. Tonazzi was a city boy, but his family had a cabin in Valbruna, not far from the renowned ski club at Monte Lussari in the Julian Alps, near the Austrian and Slovenian borders. Back then, school came first, so after class Tonazzi would catch a ride from Udine to Lussari and ski for 90 minutes before the lifts closed.

Marco's first victory, at age 9.

At age 9, he entered—and won—his very first race, on a plastic surface in Tarvisio. “The [ski] wax was diesel fuel, mixed with oil,” he says. “There was a little box with two rollers. You would roll your skis over the rollers to get them to run faster on plastic.”

In 1977, Tonazzi competed in the Italian junior championships, where he was the youngest by three years in his age group. He recalls, “I wasn’t a favorite. I didn’t have a uniform. I had a hand-knitted sweater by my grandmother. My brother was my coach.” Yet win he did, and at age 18, Tonazzi made Italy’s A team at the tail end of the Italian racers’ Valanga Azzurra (“Blue Avalanche”) heyday, becoming a teammate of Thöni and Piero Gros. “They were my idols,” he says. Eventually Thöni became his coach. “But I was a rebel,” adds Tonazzi. “They called me ‘Ragazzo Hippie,’ Hippie Boy, because I had long hair and the Sony Walkman was just invented so I would ski listening to music. It was wild! An athlete on the national team listening to the Beatles while training! I got fined by the federation for having the Walkman always on my head.” Listening to the Beatles, he claims, is how he learned to speak English.

Tonazzi made his World Cup debut in 1980, at age 19, with less than stellar results. “I sucked really bad in ’83, ’84,” he says. So he was put on the B team, and one day in Bulgaria, he was chasing a teammate between trees and through powder. The teammate stopped abruptly, Tonazzi caught him. “I was all happy and cheering, then I flew off an edge and fell about 25 to 30 feet from the top of a skier’s underpass,” he relates.

Had he not suffered a concussion and brain hematoma, says Tonazzi, “I would have been cut, I was doing so poorly. But because I was injured, they gave me another chance.” On the B team, he eventually won the 1985 Italian national championships and 1985 World University Games, both in slalom.

“I came back to the World Cup, and I don’t know how the secret of giant slalom revealed itself to me, but somehow I got it,” Tonazzi says. In December 1985, he finished eighth in Alta Badia, Italy, from the back of the pack. The next month, he placed second at Adelboden—the Kitzbühel of GS courses—wearing bib No. 40, behind Italian teammate Richard Pramotton. It was Tonazzi’s 25th birthday and time to cash in on a promise. “My dad declared that he would stop smoking if I ever made the top three,” he says. “He thought he was safe,” but his son called him on it in a TV interview.

to right, Pramotten, Tomba,

Tonazzi.

On the World Cup, 1986 turned out to be Tonazzi’s best year. It also marked the arrival of a new roommate, Tomba. “I was kind of the old wise guy at 25, so they thought I’d keep him in check,” Tonazzi says. Tomba was a city boy, too, from Bologna, and when Tonazzi drove west to camps or races, Tomba’s father would drop off his son to carpool.

“The thing about Tomba,” Tonazzi says, “he didn’t change because of his success. His attitude, mannerisms, ideas, behavior remained the same—to his credit. That was the true Alberto from age 16—a crazy, talented, explosive athlete who thought he was the best in the world before he became the best in the world. I think that’s what made him the best. He really believed he was, knew he was and just went down that path.”

Tonazzi competed on the World Cup through 1989, but he was eager to get away from the confinement and politics of the national team. “I always thought the pro tour was a place where you make your choices,” he says. “I was dreaming of that. I was also dreaming of driving across America in a big car with the radio on. I wanted to do that so badly that when the team came back, I was still ranked 24th in the world in slalom, but I said, ‘I’m done.’ I did it on my terms, which was important to me.”

In his first season as a pro, he drove around the U.S. with two 1984 Olympians, Slovenian Tomaz Cerkovnik and Swede Gunnar Neuriesser, and competed head-to-head against Austrian powerhouses Bernhard Knauss, Mathias Berthold and Roland Pfeifer. Tonazzi loved it. “Someone said they would have to stop the tour to make Marco stop,” he recalls.

But that’s not how it ended. In 1997, says Tonazzi, “I was done. My knees were really not healthy. I was almost 37, super-old.”

He also wanted to do one more thing: the 24 Hours of Aspen race. “To me, it was as close as I could get in skiing to a survival situation,” he explains. “Ski racing is intense, but what’s so tragic about one minute, 20 seconds? There’s no survival. I was missing this idea of fighting with myself through pain, being tired and more than tired. That was the only thing I knew in ski racing that existed.”

To enter, Tonazzi had to be part of a two-person team from the same nation, so he recruited countryman Josef Polig, the 1992 Alpine Combined Olympic gold medalist. Tonazzi was recovering from knee surgery and now says he had “no clue” how to train for 80 runs down Aspen Mountain—a quarter-million vertical feet—at downhill speeds.

Every team had a support crew. Tonazzi’s included Taché, who had never done the event himself despite being a local. “It was a horrific event,” says Taché. “I mean, it’s gnarly. Your partner and you just tuck in behind each other and literally go straight down from the top to the bottom. The lighting wasn’t very good. There’d be totally dark spots. And it’s early season, so all the terrain was more pronounced.”

After about five hours, Tonazzi was flagging so Polig took the lead. Then at around 1 a.m. Polig said, “I’m done. I’m scared, I can’t hold on anymore.”

Responded Tonazzi, “One more. Stay behind me. We won’t push.” At the bottom, they got on the gondola and Polig reiterated, “Marco, I can’t do it.”

“One more,” Tonazzi said,

At the top of the gondola, the competitors ran and jumped into the skis awaiting them, the way they started each lap. “I run out, look at the skis next to me and nobody’s there,” Tonazzi says now. “I turn around and see Joe in the gondola riding back down. So that’s it. I was disqualified.” He skied down alone.

“At the bottom, I asked, ‘What do I do?’” Tonazzi says. “Someone said, ‘Keep going. You won’t be ranked, but who cares?’”

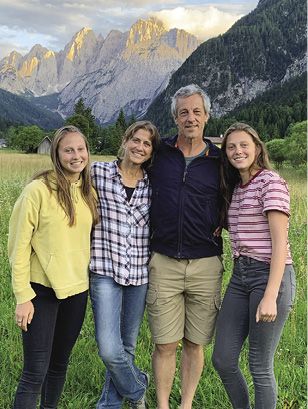

Isabella, Amy and Liliana.

The event raised money for charities, one of which supported children with terminal illnesses. Eventually, after about 15 hours of skiing, Tonazzi stumbled again into the gondola. This time, three kids—beneficiaries of the fundraising who were “paired” with the Italian team during the race—peered into his car and yelled, “Marco! Don’t stop!”

The moment is as vivid and raw as it was 25 years ago. “The doors closed to those three kids that are probably long gone now,” he recalls. “So I skied through the night by myself and finished at noon the next day. It was a great memory. It gave me even more than I expected. I did everything I wanted to do in skiing.”

Tonazzi returned to Vail, where he was living with Amy Wheeler, a ski model known for action shoots for films and magazines. In 1999, they married and now have two daughters: Isabella, 20, a freshman at Montana State University, and Liliana, 17, who plays volleyball in high school. Neither one ski races.

These days, Tonazzi runs six businesses. In Colorado, he owns the Minturn Inn (a bed and breakfast between Vail and Beaver Creek); the Hotel Minturn a few blocks away; Mangiare, an Italian food market farther down the road; and the Valbruna clothing store in Vail. He also co-owns the Valbruna Inn in Italy and runs Valbruna Travel, which enables him to guide at least one summer and one winter trip to his hometown. More recently, he bought half of Astis, a company that makes distinctive leather ski mittens featuring beaded patterns and fringe.

Thanks to Tonazzi’s willingness to empower his staff and delegate work, all of the businesses appear to be thriving. “I try to [hire] people who are better than I am at what they do and give them room to do what they like, to the best of their ability,” he says. “I tell a lot of stories and sometimes they look at me like I’m a lunatic, but I think if they know who I am—my values, morals and ethics—I don’t need to run the business myself. They will make the decisions and run the business like I would, no matter where I am.”

As for why he has so many businesses, the answer is in his nature. “Even while racing, I was always easily distracted by other passions,” Tonazzi explains. “When there’s something I like, I cannot say no. It’s like a missed opportunity. So I kind of take on too much and juggle and try not to drop anything.”

New York-based sportswriter Aimee Berg wrote about freestyle champ Kari Traa in the September-October, 2021 issue.

Photos courtesy Marco Tonazzi.

Table of Contents

WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP ($3,000+)

BerkshireEast/Catamount Mountain Resorts

Gorsuch

Warren and Laurie Miller

Sport Obermeyer

Polartec

CHAMPIONSHIP ($2,000)

Fairbank Group: Bromley, Cranmore, Jiminy Peak

Hickory & Tweed

Rossignol

Snowsports Merchandising Corporation

WORLD CUP ($1,000)

Aspen Skiing Company

Bogner of America

Boyne Resorts

Dale of Norway

Darn Tough Vermont

Dynastar/Lange/Look

Gordini USA Inc/Kombi LTD

Head Wintersports

Intuition Sports

Mammoth Mountain

Marker/Völkl USA

National Ski Areas Association

North Carolina Ski Areas Association

Outdoor Retailer

Ski Area Management

Ski Country Sports

Sports Specialists Ltd

Sugar Mountain Resort

Sun Valley Resort

Vintage Ski World

World Cup Supply

GOLD MEDAL ($700)

Larson's Ski & Sports

Race Place/Beast Tuning Tools

The Ski Company (Rochester NY)

Thule

SILVER MEDAL ($500)

Alta Ski Area

Boden Architecture PLLC

Dalbello Sports

Deer Valley

EcoSign Mountain Resort Planners

Elan

Fera International

Holiday Valley Resort

Hotronic USA/Wintersteiger

Kulkea

Leki

Masterfit Enterprises

McWhorter Driscoll LLC

Metropolitan New York Ski Council

Mt. Bachelor

New Jersey Ski & Snowboard Council

Nils

Russell Mace Vacation Homes

SchoellerTextil

Scott Sports

Seirus Innovations

SeniorsSkiing.com

Ski Utah

Snowbird Ski & Summer Resort

Steamboat Ski & Resort Corp

Sundance Mountain Resort

Swiss Academic Ski Club

Tecnica Group USA

Timberline Lodge and Ski Area

Trapp Family Lodge

Wendolyn Holland

Western Winter Sports Reps Association

World Pro Ski Tour

Yellowstone Club