SKIING HISTORY

Editor Seth Masia

Managing Editor Greg Ditrinco

Consulting Editor Cindy Hirschfeld

Art Director Edna Baker

Editorial Board

Seth Masia, Chairman

John Allen, Andy Bigford, John Caldwell, Jeremy Davis, Kirby Gilbert, Paul Hooge, Jeff Leich, Bob Soden

Founding Editors

Morten Lund, Glenn Parkinson

To preserve skiing history and to increase awareness of the sport’s heritage

ISHA Founder

Mason Beekley, 1927–2001

ISHA Board of Directors

Rick Moulton, Chairman

Seth Masia, President

Wini Jones, Vice President

Jeff Blumenfeld, Vice President

John McMurtry, Vice President

Bob Soden (Canada), Treasurer

Richard Allen, Skip Beitzel, Michael Calderone, Dick Cutler, Wendolyn Holland, Ken Hugessen (Canada), David Ingemie, Joe Jay Jalbert, Henri Rivers, Charles Sanders, Einar Sunde, Christof Thöny (Austria), Ivan Wagner (Switzerland)

Presidential Circle

Christin Cooper, Billy Kidd, Jean-Claude Killy, Bode Miller, Doug Pfeiffer, Penny Pitou, Nancy Greene Raine

Executive Director

Janet White

janet@skiinghistory.org

Membership Services

Jamie Coleman

(802) 375-1105

jamie@skiinghistory.org

Corporate Sponsorships

Peter Kirkpatrick

(541) 944-3095

peterk10950@gmail.com

Bimonthly journal and official publication of the International Skiing History Association (ISHA)

Partners: U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame | Canadian Ski Museum and Hall of Fame

Alf Engen Ski Museum | North American Snowsports Journalists Association | Swiss Academic Ski Club

Skiing History (USPS No. 16-201, ISSN: 23293659) is published bimonthly by the International Skiing History Association, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255.

Periodicals postage paid at Manchester Center, VT and at additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send address changes to ISHA, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255

ISHA is a 501(c)(3) public charity. EIN: 06-1347398

Written permission from the editor is required to reproduce, in any manner, the contents of Skiing History, either in full or in part.

Zali Steggall: The Power of Teal

The slalom world champion and Olympic bronze medalist has won her second term in Australia’s parliament, as a Green/Blue independent.

Photo above: A pioneer throughout her career, Zali Steggall became the first Australian woman to win a World Cup event in Alpine skiing, a 1997 slalom in Park City, Utah. She also won Australia’s first Olympic Alpine medal and first FIS World Championship title, both in slalom.

Ash Berdebes photo.

What does one do for an encore after winning a World Cup race, a World Championship slalom title and an Olympic medal in Alpine skiing?

If you’re Zali Steggall, you get a law degree while raising five kids, beat a former prime minister for his seat in the Australian Parliament, get elected to a second three-year term and take up ultra-running—all by the age of 48.

Somewhat miraculously, the four-time Olympian and slalom specialist found a moment to chat shortly after Australia’s most recent federal election in May 2022. She phoned from Warringah, the district she represents, which encom- passes Sydney’s north shore and lower northern beaches. It’s a three-and-a-half hour drive from the capital city of Canberra, where members of Parliament sit for about 22 weeks a year, from Monday to Thursday, so she returns regularly to her electorate. It’s the same district that Tony Abbott represented for 25 years (including as prime minister from 2013-15), un- til Steggall, an independent, defeated him in 2019 by a 14.4 percent margin, after all the votes for the less popular candi- dates were re-allocated. (When voting, Australians must rank each candidate in order of preference.)

This May, Steggall won her second term, with a 22 percent lead over the Liberal Party candidate. She viewed this increased margin as a positive sign that her old critics were wrong when they said that the only reason she won as an independent in 2019 was because she’d taken on Abbott, regarded by some as a toxic personality who weaponized cli- mate policy in Australia. Once he lost, their logic went, voters would go back to traditional party lines.

left) at victory party. Ash Berdebes photo

“The criticism is always: What can an independent do be- cause I’m not part of a big-party machine?” she says. “I think I really showed that I can be very effective in pressuring the government and putting forward sensible solutions, especially around climate.” She is not alone. This year, six women were elected as “teal independents” for their blend of green (pro-environment) and liberal-leaning (blue) politics.

When Steggall retired from ski racing after the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympics, she wasn’t hellbent on politics. All she knew was that her life’s pinnacle was not her 1997 slalom vic- tory in Park City (the first World Cup win by an Australian woman) nor the 1998 Olympic slalom bronze she captured in Nagano (Australia’s first Olympic Alpine medal) nor her 1999 World Championship title in Vail (another Aussie first). When asked to identify the highlight of her life at her final press conference, she said, “I’m 27, and I certainly hope I haven’t had it yet.”

“That [statement] really epitomizes my philosophy,” she says now. “It doesn’t matter what you achieve, it’s important to keep setting new goals and keep challenging yourself in new ways. For me, a satisfying life is a challenging life.”

NO STRANGER TO CHALLENGE

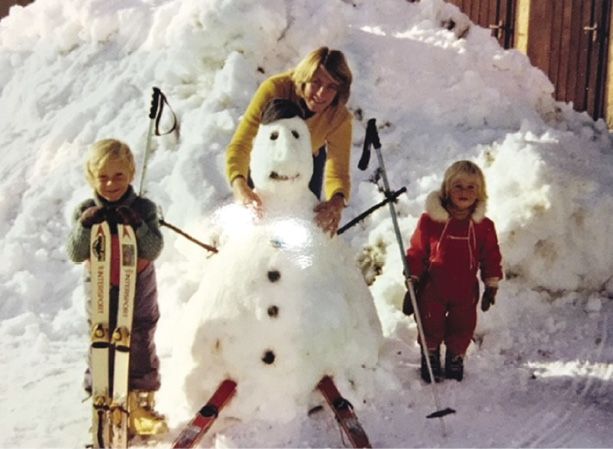

Olympians, Zeke (left) and Zali,

in Morzine, France. Family photo

When she was 4, her parents took Steggall and her older brother, Zeke, to live in Morzine, France, for 10 years. She spoke French in school and English at home, and trained with the French junior ski team. Had she continued, the deal was that she would have to represent France when she turned 18. Instead, the Steggalls returned to Australia in 1988 and absorbed tremendous expenses to finance their daughter’s coaching, equipment and travel in a nation that had a grand total of four World Cup podiums in Alpine skiing.

The road to the 1992 Albertville Olympics was even more fraught, because Australia only received two Alpine berths. Steven Lee was likely to take one, and a half dozen men in their early 20s on the Europa Cup or World Cup level expected to vie for the other. Says Steggall, “I was a 17-year-old upstart who said, ‘No, the two spots should go to the best-ranked skiers with the best prospects.’” She quit her final year of high school to train full-time, improved her FIS ranking and snatched the second spot. “It meant a lot to me because those Olympics were in France, and I’d grown up in France,” she says, “but also, I was training with Annelise Coberger from New Zealand. To watch her win the silver medal in slalom there was huge, the first-ever Alpine medal for the southern hemisphere. She proved it could be done. It was pivotal.”

By the 1994 Lillehammer Games, Steggall still didn’t have the resources to compete with the top nations and she was ski- ing five events—although she pared it down to slalom, GS and combined for the Games. Still, she had to pay her own excess baggage fees to get six to eight pairs of skis, gates and other equipment to the Olympics. She laughs about it now but after Lillehammer, she says, “I had to make a strategic decision. I felt my best shot was to become an absolute expert at slalom.”

Around that time, the Grollo family, who owned Mount Buller, got behind Alpine racing. They started the Australian Ski Institute, paying for Steggall’s coaching and providing her with a proper program. But she still needed a world-class training group, so by the 1997–98 Nagano Olympic season, Steggall was working with the German women’s technical team. At 23, she had already been racing for 10 years. “It was crunch time,” she said. “Ei- ther crack the top seed of World Cup or do something else because I was going into my third Olympics.”

As it turned out, she put together the two best seasons of her career.

Olympics. Photo courtesy Sport

Australia Hall of Fame.

At the World Cup opener in November 1997, a clear, crisp day in Park City, Utah, everything went according to plan. She won the first run—the bane of a slalom skier. “Shit,” she thought. “Can I do it a second time?” She did, becom- ing the first Australian woman to win a World Cup race. But Ylva Nowén of Sweden won the next four slaloms, and Steg- gall went back to Australia for 10 days leading up to Nagano. “Those years were pre-internet, pre-Facebook, pre-mobile phones,” she recalls, “so you’re quite disconnected. I was quite lonely, living on my own in Europe for months on end. Com- ing home meant you spent 24 hours on a plane travelling, but you really got a lift emotionally, mentally. In January, it’s mid- summer, warm.”

As a result, she missed both Nagano’s opening ceremony and her brother Zeke’s event. (Zeke was competing in the Olympic debut of snowboarding, 11 days before Zali’s race.) Upon arrival, she stayed with the German team on the moun- tain, away from the drama of the Olympic Village.

At the time, Australia had exactly one winter Olympic medal, a 1994 bronze in the men’s 5,000-meter short track speedskating relay. At Nagano, everyone expected Australia to win its first individual medal, most likely in aerials because Kirstie Marshall was the 1997 world champion and Jacqui Cooper was ranked second in World Cup aerials. Both failed to make the finals, however, and the short track team didn’t medal, either.

“All of a sudden, the whole Australian contingent at the Winter Games turned to me because I was the last prospect,” Steggall says. “Two days before the end of the Games, the whole team is facing criticism. ‘We haven’t progressed from the bronze relay medal. What does this mean for Australia at the Winter Olympics?’ I was incredibly nervous. It was in- sane. There was so much on the line.”

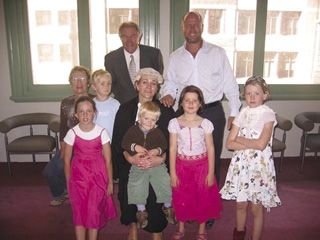

upon donning wig and robes as

a barrister, 2008.

After the first run of slalom, Steggall and her training partner, Hilde Gerg of Germany, were third and second, re- spectively, behind Deborah Compagnoni of Italy. The course- setter for run two was their German coach, Wolfgang Grassl. Between runs, Steggall spent a couple of hours talking to her brother in the athletes’ tent. “All I can remember is talking about everything and nothing,” Zeke says, “not concentrating too much on skiing.”

By the end of the day, Gerg had won gold and Steggall collected bronze.

“You can’t underestimate what [that Olympic medal] did for winter sports funding in Australia,” she says. The Austra- lian Institute of Winter Sports was formed after Nagano. (In 2001, it was renamed the Olympic Winter Institute of Aus- tralia, or OIWA.) “That was the launch of the whole proper professional winter program in Australia,” adds Steggall “Fi- nally, everything I had dreamed it would be, was. I had good coaches, good equipment, a good program, good sponsors, sufficient funding to have a world-class program.”

A year later, at the 1999 World Championships in Vail, Steggall took another trip home during the lead-up to the event. Once again, her coach set the slalom course for the second run. This time, it was Helmut Spiegl, and he set it across the hardest section of Pepi’s Face. “Hellie decided to go straight over the top and straight down the steepest section, and that’s where I made up my whole race, basically,” Steggall recalls. After the first run, she was tied for sixth with Pernilla Wiberg of Sweden but, says Steggall, “the last 10 turns down the steep is where I won it. I was not intimidated, and I nailed it.” Australia had its first world champion in Alpine skiing.

At the time, Australia was gearing up to host the 2000 Sydney Olympics, so when Steggall came back with the Olympic bronze from Nagano and a world title, she was a star—especially in her hometown of Manly, a beach suburb, where she would later carry the 2000 Olympic torch on its fi- nal leg around town, across the ferry and up Sydney Harbour by the Sydney Opera House. “It was as close to a home crowd celebration of sport as I was ever going to get because I was never going to have a World Cup [race] in Australia,” she says.

By then, Steggall had married an Olympic rower from the 1996 Games, David Cameron, but he had retired from the sport, and their time apart took a toll. She was far from home and had trouble sleeping before races. She caught glandular fever and tried to compete through it because she was a team of one with two coaches. Also, the top athletes had switched to shaped carving skis during the European summer and Steg- gall had missed the changeover. “It’s just the tyranny of being southern hemisphere and isolated from the rest of the Alpine community,” she says. And then, while she was training in New Zealand, terrorism hit the United States on September 11, and Steggall wondered if she shouldn’t do something more substantial than racing.

“Any good thing is going to come to an end at some point,” she says. “The question is: ‘How?’ By the time I got to the 2002 Olympic Games, I didn’t miss a single season, didn’t take a single break for injury. I was mentally and emotionally exhausted.” Her career ended with a first-run DNF in the Olympic slalom.

Steggall had finished her college degree while competing, but she had always been keen to study law. “So for the next four years [2002–2006], I studied law, had my two kids and worked part-time,” she relates. “I turned up for lectures with my [younger] son, Remy, in the Baby Bjorn and cut out to change his nappy. I multitasked my way through my law degree. I worked for my dad as a solicitor. Ultimately, I really wanted to be an advocate, or a barrister, who goes to court,” she says.

marathons in the Blue Mountains of

New South Wales.

Doing so required additional exams, and by the time she was done in 2008, she had divorced, remarried and gained three stepdaughters. She donned the iconic 17th-century uniform of Commonwealth courts: a powdered wig and black gown. Compelled to make a difference, Steggall became a legal expert in land environment, native title, commercial, equity, family and sports law. In fact, as a member of the international Court of Arbitration for Sport, Steggall attended a fifth Olympics, in 2018; as part of the court’s ad hoc division, she helped dismiss the last-ditch appeals of 47 Russian athletes and coach- es to participate in the PyeongChang Winter Olympics.

After 11 years, Steggall left her profession as a barrister to become a politician. “By late 2018, I was really focused on climate,” she explains. “Our climate policies have been very dysfunctional for 10, 15 years. The previous member of my seat in Warringah, Tony Abbott, was incredibly destructive. There was a strong movement to have an alternate choice. Newspaper articles talked about how the best candidate to take on Abbott would be a professional female, 35 to 50, ideally, with a profile and professional experience. I thought, ‘I can do this.’ I turned to my husband [Tim Irving] and said: ‘What if I give this a go? It took off, and we had a very intense campaign for five months.”

The campaign wasn’t the only thing she was running. A week after Steggall declared her candidacy, she learned that she and her ultra-marathon training partner had won the lot- tery to enter the Tour de Savoie, a 145-kilometer (90 miles) race with 9,100 meters of elevation gain. Eight months later, with less-than-perfect training, she pulled out after 113 kilo- meters (70 miles). “It’s the only event I’ve quit,” she says. “I want to go back and complete either that or the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc.” Also on her bucket list: the Western States 100 in California, the world’s oldest 100-mile trail race.

“I’m not afraid of a challenge,” says Steggall, who went from winning 50-second slalom runs to racing 20 hours non- stop and designing government policy for an entire continent.

Table of Contents

WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP ($3,000+)

BerkshireEast/Catamount Mountain Resorts

Gorsuch

Warren and Laurie Miller

Sport Obermeyer

Polartec

CHAMPIONSHIP ($2,000)

Fairbank Group: Bromley, Cranmore, Jiminy Peak

Hickory & Tweed

Rossignol

Snowsports Merchandising Corporation

WORLD CUP ($1,000)

Aspen Skiing Company

Atomic USA

Bogner of America

Boyne Resorts

Dale of Norway

Darn Tough Vermont

Dynastar/Lange/Look

Gordini USA Inc/Kombi LTD

Head Wintersports

Intuition Sports

Mammoth Mountain

Marker/Völkl USA

National Ski Areas Association

North Carolina Ski Areas Association

Outdoor Retailer

Ski Area Management

Ski Country Sports

Sports Specialists Ltd

Sugar Mountain Resort

Sun Valley Resort

Vintage Ski World

World Cup Supply

GOLD MEDAL ($700)

Larson's Ski & Sports

Race Place/Beast Tuning Tools

The Ski Company (Rochester NY)

Thule

SILVER MEDAL ($500)

Alta Ski Area

Boden Architecture PLLC

Dalbello Sports

Deer Valley

EcoSign Mountain Resort Planners

Elan

Fera International

Holiday Valley Resort

Hotronic USA/Wintersteiger

Kulkea

Leki

Masterfit Enterprises

McWhorter Driscoll LLC

Metropolitan New York Ski Council

Mt. Bachelor

New Jersey Ski & Snowboard Council

Nils

Russell Mace Vacation Homes

SchoellerTextil

Scott Sports

Seirus Innovations

SeniorsSkiing.com

Ski Utah

Snowbird Ski & Summer Resort

Steamboat Ski & Resort Corp

Sundance Mountain Resort

Swiss Academic Ski Club

Tecnica Group USA

Timberline Lodge and Ski Area

Trapp Family Lodge

Wendolyn Holland

Western Winter Sports Reps Association

World Pro Ski Tour