SKIING HISTORY

Editor Seth Masia

Managing Editor Greg Ditrinco

Consulting Editor Cindy Hirschfeld

Art Director Edna Baker

Editorial Board

Seth Masia, Chairman

John Allen, Andy Bigford, John Caldwell, Jeremy Davis, Kirby Gilbert, Paul Hooge, Jeff Leich, Bob Soden

Founding Editors

Morten Lund, Glenn Parkinson

To preserve skiing history and to increase awareness of the sport’s heritage

ISHA Founder

Mason Beekley, 1927–2001

ISHA Board of Directors

Rick Moulton, Chairman

Seth Masia, President

Wini Jones, Vice President

Jeff Blumenfeld, Vice President

John McMurtry, Vice President

Bob Soden (Canada), Treasurer

Richard Allen, Skip Beitzel, Michael Calderone, Dick Cutler, Wendolyn Holland, Ken Hugessen (Canada), David Ingemie, Joe Jay Jalbert, Henri Rivers, Charles Sanders, Einar Sunde, Christof Thöny (Austria), Ivan Wagner (Switzerland)

Presidential Circle

Christin Cooper, Billy Kidd, Jean-Claude Killy, Bode Miller, Doug Pfeiffer, Penny Pitou, Nancy Greene Raine, Lindsey Vonn

Executive Director

Janet White

janet@skiinghistory.org

Membership Services

Jamie Coleman

(802) 375-1105

jamie@skiinghistory.org

Corporate Sponsorships

Peter Kirkpatrick

(541) 944-3095

peterk10950@gmail.com

Bimonthly journal and official publication of the International Skiing History Association (ISHA)

Partners: U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame | Canadian Ski Museum and Hall of Fame

Alf Engen Ski Museum | North American Snowsports Journalists Association | Swiss Academic Ski Club

Skiing History (USPS No. 16-201, ISSN: 23293659) is published bimonthly by the International Skiing History Association, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255.

Periodicals postage paid at Manchester Center, VT and at additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send address changes to ISHA, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255

ISHA is a 501(c)(3) public charity. EIN: 06-1347398

Written permission from the editor is required to reproduce, in any manner, the contents of Skiing History, either in full or in part.

Big Times at Big Sky

From cult status to big-screen hit, can ‘The Last Best Place’ survive the trip?

In all its glory and grandeur, its vast sprawl and close community, its daily Sturm und Drang, Big Sky Resort has become a metaphor for post-modern Montana. Both cultivated an image as “The Last Best Place” (the title of a 1990 anthology of Montana literature), only to see it go wide, creating unparalleled growth and runaway real estate markets in recent years. Median home prices have risen statewide by 500 percent since 1990 and 50 percent since 2020. During the pandemic, Montana had some of the biggest population increases in the country. Some locals blame recent growth on Kevin Costner’s hit TV show Yellowstone, released at the end of 2018, along with a continuous influx of the rich and famous.

the base village. Big Sky Resort photo.

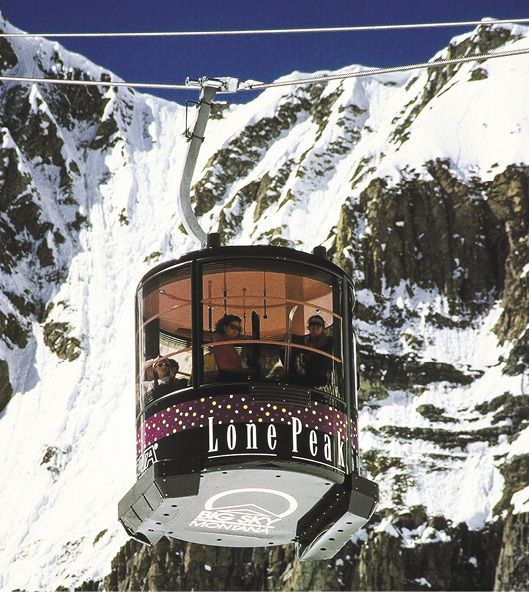

Weather is a problem. The wind howls and big snow years are sporadic. And Big Sky is a long way from anywhere. The remote location, long considered an asset by locals, became an asset for visitors when Covid hit. Once word got out, the world-class combination of Autobahn-style groomers and wild steeps made Big Sky a big deal for anyone who loves skiing. Now the slopes are just too good to hide. Stepping off the tram at the top of Lone Peak has turned many a devoted skier into a busy realtor.

Big Sky’s 5,800 skiable acres, second only to Park City among U.S. resorts, are impressive in quantity and quality—to the extreme. The view from the summit is a sparkling sweep across three states and seven mountain ranges, from the Tetons of Wyoming to a wide, white span of eastern Idaho and much of western Montana. Closer at hand are the

40-degree slots, bowls and gullies that comprise the skiing from the peak. All of it is double-black rated, including the legendary Big Couloir, along with colorful, tough-sounding originals like the Dictator Chutes, Marx, Lenin and Castro, some of the names coined by skiers who had to hike to them before the tram was built in 1995. On bluebird days the skiing is killer; in bad visibility it can be another kind of killer. On the backside of Lone Peak lie the North Summit Snowfields, a long, steep, off-piste descent that’s my favorite part of the mountain. It’s demanding, exposed and isolated, with a sign-out policy requiring probe poles, shovels and beacons.

Overlooking the Big Couloir along the same curving ridgeline, the A–Z Chutes hold more high-angle, hike-to lines, with a primarily southern exposure. Their backside is the home of Moonlight Basin’s Headwaters terrain, north-facing, crazy, frozen-waterfall plunges. The Headwaters runs are mostly hike-to and have been rated triple-black to discourage wannabes.

The good news is that if you’re not up for the thrill rides, Big Sky has you covered, and then some. Andesite Mountain on the eastern perimeter of the resort hosts some of the best fully buffed, high-speed terrain you’ll find anywhere. It’s so good that regional ski teams race and train on it. I’ve gone much faster there than is wise. The dozen runs of bombers, powder glades and pocket steeps are served by four lifts, including the first eight-passenger heated and bubbled high-speed chair in North America.

The lower parts of Lone Mountain and Moonlight offer loads of big, blue boulevards, providing intermediates access to the whole resort on a 245-degree arc from the Dakota lift to Moonlight’s Six-Shooter chair. Multiple terrain parks, a NASTAR course and several large, fenced-off learning areas with magic carpets round out the family options. Then there’s the terrain served by the heated and covered Powder Seeker six-pack lift, and the high-speed double Challenger chair and the ballroom skiing of Southern Comfort and…

Chet Huntley envisioned a recreational

hub, and borrowed the name Big Sky.

Montana skiing wasn’t always this big-league. Through most of the 1970s, the state hosted only a dozen or so mom-and-pop ski areas. With the exception of Big Mountain in Whitefish, Bridger Bowl near Bozeman and Red Lodge in the Beartooths, these ski areas were mostly built by ranchers for entertainment during their slack winter seasons. A few well-known writers, athletes and movie stars lived in Montana, along with a lot more cattle and elk than cars. It was mainly the stomping grounds of farmers and ranchers, Native Americans, timber companies, miners, college kids and assorted drifters.

The Madison Range of southwestern Montana was the property of ranchers, timber companies and the U.S. Forest Service. In that cluster of rugged mountains, about an hour’s drive up the Gallatin River between Bozeman and Yellowstone National Park, fang-like Lone Mountain dominates the landscape.

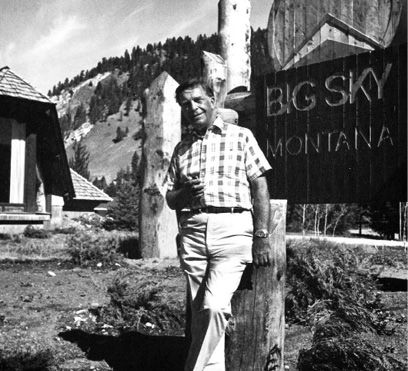

It was there in 1970 that Chet Huntley, the recently retired NBC news anchor, chose to build a resort. Huntley was a Montana native and, with the help of some major financial backers, he returned to his home state to develop Big Sky Ski and Summer Resort. It wasn’t universally welcomed, and there were hard feelings when the resort appropriated one of the state’s mottos for its name. Huntley was soon muscled out of the corporation by his investors, and he died of cancer three days before the resort opened in March 1974.

In 1976, Boyne Resorts founder and patriarch Everett Kircher bought Big Sky for $8.5 million. Kircher, who had opened Boyne Mountain, Michigan, in 1947, was a pilot who was happy to fly around the country to oversee a growing resort empire. Still Michigan-based today, Boyne is the longest running multi-resort company in the U.S., with 10 ski areas, including Loon, Sugarloaf and Sunday River in the East.

Everett’s son, Stephen, Boyne’s current president and CEO, recalls the early years in Montana, when the resort had just four lifts and a lot of dirt roads. “Big Sky was a far cry from what it is today,” he says. And as with all resorts anywhere, that’s both good and bad.

on the national ski radar.

The first time I skied Big Sky, in the early ’80s, there was still more wildlife on the slopes than skiers. Annual skier numbers have since skyrocketed, going from 70,000 in the 1970s to more than half a million today, but there are still enough animals to populate a National Geographic show. They include bighorn sheep on the roads, snow-white mountain goats roaming the A–Z ridge and elk and moose anywhere, any time.

The country surrounding Big Sky was mostly wilderness, U.S. Forest Service land and logging tracts until 1992. Then, amid considerable controversy, lumber billionaire Tim

Blixseth and partners bought and land-swapped property with the Forest Service for nearly 100,000 of those acres. Blixseth kept 13,600 acres and logged 2,700 of it in the shape of ski runs. In 1997 he turned it into the super-exclusive Yellowstone Club, one of the world’s few private ski and golf communities.

I was invited there the year before it officially opened. Blixseth, Warren Miller and former quarterback and congressman Jack Kemp took a couple of us on a press tour, riding snowcats to ski. It was good, varied terrain, with 2,700 feet of vertical, and ridiculously fun to have all to ourselves. I hear that’s still the case, at least part of the time. And members also have ski-in entrée to all of the adjoining Spanish Peaks, Big Sky and Moonlight Basin lifts, for 8,500 total acres.

In 1992 Blixseth sold 25,000 acres, including the powder-filled north side of Lone Mountain, to locally owned Moonlight Basin. Moonlight opened two lifts that accessed Big Sky Resort’s skiing and started selling real estate. In 2003, Moonlight dropped the rope on its own temporarily independent resort, with five more lifts across 1,900 acres.

The Spanish Peaks real-estate development, owned by the Dolan family of Philadelphia, acquired the remaining large tract of 6,750 acres between Big Sky and the Yellowstone Club in the 1990s. From 2005 through 2007, Spanish Peaks opened a log clubhouse, lifts and a golf course, along with access runs connecting it to Big Sky, filling out the map for one of the biggest interconnected resort systems in North America.

Then, beginning in 2006, it looked like all of it might go belly up. Blixseth’s life turned tabloid, as he got in deep financial trouble and divorced in 2008, unloading the debt-ridden Yellowstone Club onto his ex-wife, Edra. Within the year, CrossHarbor Capital Partners withdrew an offer of $470 million for the club and Edra declared bankruptcy. A year later, CrossHarbor got the club for just $115 million. Tim Blixseth ended up in jail for fraud and contempt of court. He accused CrossHarbor and the governments of three states of sabotaging him, claims that were thrown out of court. Sam Byrne, the billionaire managing general partner of CrossHarbor, was reported to have already owned $200 million worth of Yellowstone Club real estate prior to buying the whole thing.

Montage Big Sky. MBS photo.

Spanish Peaks, already hit with lawsuits by property owners, was crippled by the 2008 recession. CrossHarbor and Boyne stepped in. At the bankruptcy auction in Butte, Montana, in 2013, when CrossHarbor made the winning bid of $26.1 million for Spanish Peaks, James Dolan reportedly looked over at Sam Byrne and said, “Well, he’s the new king of the valley. I wish him luck.” That year CrossHarbor, in partnership with Boyne, bought Moonlight Basin from the bank that owned the note.

What Big Sky Resort calls “The Biggest Skiing in America” has been controlled by just two different owners for the past 10 years and has flourished. Big Sky was posting record numbers going into the pandemic and has seen no let-up since. Scores of lavish private homes have been built each year for the last decade. And a major new subdivision between Lone Mountain and the Meadow Village has gotten approval for up to 1,700 more units.

New lodges have also been added, including CrossHarbor/Montage’s massive $400 million Montage Big Sky, which opened last year at Spanish Peaks, and the four-star Wilson Hotel Marriott Residence Inn in Meadow Village. At Moonlight Basin, a new hotel/residential development by the very upscale One & Only resort chain brought lodging investment in the greater Big Sky area to well over a billion dollars.

Those upgrades have been the result of a major repositioning in Big Sky, following years of skier-survey complaints about an overall lack of hotels, especially high-end ones. As Byrne said at the Montage Big Sky groundbreaking, “We look at this market as akin to Jackson Hole 25 years ago, that in general has been dramatically underserved by hotels.”

Kevin Germain is one of the principals of the Lone Mountain Land Company, which handles all of the CrossHarbor real estate sales other than for the Yellowstone Club. “More mature communities like Jackson Hole have a much higher occupancy rate and greater hospitality bed base than Big Sky currently has,” he explained to the Lone Peak Lookout newspaper in 2018. “One way they increase their occupancy is through increased use of overnight accommodations. So we now have more hotels in our plans.”

The real estate explosion is accompanied by a $15 million capital improvement program from Boyne. It’s called Big Sky 2025. President and General Manager Taylor Middleton described it as a “commitment to progressive improvements and sustainable growth over the next decade, that includes a new age of lift technology in major zones of the mountain.”

That new age has so far produced four ultra-modern replacement lifts since 2016, and the opening of the elegant Everett’s 8800 restaurant at the top of Andesite Mountain. A ground-up renovation of the Mountain Village’s Mountain Mall added a food court and event venue, expanding lunch and entertainment options and indoor seating. Remodels of the Huntley and Summit Lodges are scheduled. And this past summer the first towers were set for a much anticipated replacement tram serving Lone Peak.

This substantial growth spurt skews distinctly up-market. Like many resorts around the world, Big Sky is growing and succeeding, often beyond what was imagined. Part of the community is terrified of becoming another Jackson or Sun Valley, while another part hopes that’s exactly what will happen and that they’ll cash in on the bonanza.

The challenge will be to provide a high-quality experience while remaining accessible to middle-class skiers and sustaining a real community. Big Sky proper, which has remained unincorporated, has finally established good schools, grocery stores and on-site medical services; locals want a town with an identity beyond an Alpine strip mall.

Big Sky is no longer a secret, remote mountain. How much of its wild Montana soul and charm it will sacrifice to real estate developers and bankers will depend on the strength of its residents, the sophistication of their long-range planning and the sensibilities of the two county governments that control zoning for the resorts and collect property taxes from them. It’s a formidable task to thread the needle between competing interests, and few resorts have achieved a balance that satisfies everyone.

Regular contributor Jay Cowan wrote about ski-mountaineering records in the September-October 2021 issue.

Table of Contents

WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP ($3,000+)

BerkshireEast/Catamount Mountain Resorts

Gorsuch

Warren and Laurie Miller

Sport Obermeyer

Peak Ski Company

Polartec

CHAMPIONSHIP ($2,000)

Fairbank Group: Bromley, Cranmore, Jiminy Peak

Hickory & Tweed Ski Shop

Rossignol

Snowsports Merchandising Corporation

WORLD CUP ($1,000)

Aspen Skiing Company

Atomic USA

Bogner of America

Boyne Resorts

Dale of Norway

Darn Tough Vermont

Dynastar/Lange/Look

Gordini USA Inc/Kombi LTD

Head Wintersports

Intuition Sports

Mammoth Mountain

Marker/Völkl USA

National Ski Areas Association

North Carolina Ski Areas Association

Oppenheimer & Co. Inc.

Outdoor Retailer

Ski Area Management

Ski Country Sports

Sports Specialists Ltd

Sugar Mountain Resort

Sun Valley Resort

Vintage Ski World

World Cup Supply

GOLD MEDAL ($700)

Larson's Ski & Sports

McWhorter Driscoll LLC

Race Place/Beast Tuning Tools

The Ski Company (Rochester NY)

Thule

SILVER MEDAL ($500)

Alta Ski Area

Boden Architecture PLLC

Dalbello Sports

Deer Valley

EcoSign Mountain Resort Planners

Elan

Fera International

Holiday Valley Resort

Hotronic USA/Wintersteiger

Kulkea

Leki

Masterfit Enterprises

Metropolitan New York Ski Council

Mt. Bachelor

New Jersey Ski & Snowboard Council

Nils

Russell Mace Vacation Homes

SchoellerTextil

Scott Sports

Seirus Innovations

SeniorsSkiing.com

Ski Utah

Snowbird Ski & Summer Resort

Steamboat Ski & Resort Corp

Sundance Mountain Resort

Swiss Academic Ski Club

Tecnica Group USA

Timberline Lodge and Ski Area

Trapp Family Lodge

Wendolyn Holland

Western Winter Sports Reps Association

World Pro Ski Tour