SKIING HISTORY

Editor Seth Masia

Managing Editor Greg Ditrinco

Consulting Editor Cindy Hirschfeld

Art Director Edna Baker

Editorial Board

Seth Masia, Chairman

John Allen, Andy Bigford, John Caldwell, Jeremy Davis, Kirby Gilbert, Paul Hooge, Jeff Leich, Bob Soden, Ingrid Wicken

Founding Editors

Morten Lund, Glenn Parkinson

To preserve skiing history and to increase awareness of the sport’s heritage

ISHA Founder

Mason Beekley, 1927–2001

ISHA Board of Directors

Rick Moulton, Chairman

Seth Masia, President

Wini Jones, Vice President

Jeff Blumenfeld, Vice President

John McMurtry, Vice President

Bob Soden (Canada), Treasurer

Einar Sunde, Secretary

Richard Allen, Skip Beitzel, Michael Calderone, Dick Cutler, Ken Hugessen (Canada), David Ingemie, Joe Jay Jalbert, Henri Rivers, Charles Sanders, Christof Thöny (Austria), Ivan Wagner (Switzerland)

Presidential Circle

Christin Cooper, Billy Kidd, Jean-Claude Killy, Bode Miller, Doug Pfeiffer, Penny Pitou, Nancy Greene Raine

Executive Director

Janet White

janet@skiinghistory.org

Membership Services

Laurie Glover

(802) 375-1105

laurie@skiinghistory.org

Corporate Sponsorships

Peter Kirkpatrick

(541) 944-3095

peterk10950@gmail.com

Bimonthly journal and official publication of the International Skiing History Association (ISHA)

Partners: U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame | Canadian Ski Museum and Hall of Fame

Alf Engen Ski Museum | North American Snowsports Journalists Association | Swiss Academic Ski Club

Skiing History (USPS No. 16-201, ISSN: 23293659) is published bimonthly by the International Skiing History Association, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255.

Periodicals postage paid at Manchester Center, VT and at additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send address changes to ISHA, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255

ISHA is a 501(c)(3) public charity. EIN: 06-1347398

Written permission from the editor is required to reproduce, in any manner, the contents of Skiing History, either in full or in part.

Commentary: Skiers in Revolt

Can Vail Resorts improve employee and customer relations? Efficient operations, and market share, may depend on it.

Overcrowding and staff shortages at ski resorts first attracted the attention of local and online media at the end of 2021, then in January spread to traditional outlets like the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, statewide papers like the Denver Post and Seattle Times, and special interest magazines such as Outside.

To be fair, resorts faced the same issues as businesses in general: namely labor shortages and slow delivery of inventory. When a shortage-afflicted business takes payment up front, fulfillment and customer services deteriorate. Late delivery angers customers.

That’s what happened at ski resorts this winter. Covid accelerated and exposed long-term trends, creating a perfect storm of employee and customer angst. A booming real estate market and an increase in Airbnb-type short-term rentals pushed the housing shortage from chronic to acute, which, combined with decades of static wages, forced employees into onerous commutes. Many employees simply declined to work that way, and when Covid put remaining employees in isolation, there weren’t enough bodies to shovel or make snow, drive groomers, maintain equipment, bump lifts, patrol and teach, flip burgers, make beds, punch cash registers, fit rental boots and provide childcare. At the same time, skiing seemed a Covid-safe outdoor activity, season passes were cheap, and skier visits on peak days soared. Ski retailers sold out early, highways and parking lots jammed up, and skiers stood in 40-minute lift queues. Skiers tolerate the late arrival of natural snow, but when the snow is great and the lifts don’t turn, they fume.

Vail Resorts was a particular target of consumer fury, incurring an organized protest movement and threats of class-action lawsuits, beginning at Stevens Pass, Washington. There, more than 44,000 skiers signed an online petition calling VR responsible for failure to open lifts and terrain, and about 300 complaints went to Washington’s Attorney General Bob Ferguson. By late January a new general manager, Tom Fortune, was turning the corner, solving some of his staff issues and opening popular backside access. The fixes were simple: more efficient use of available employee housing, increased employee shuttle service and new hiring. VR also offered the resort’s passholders deep discounts to sign up for next winter, and promised to extend the season through April. It’s worth noting that Vail very publicly bumped its minimum wage to $15 per hour in the key states of Colorado, Utah, California and Washington—but in the pre-Covid era VR’s average hourly wage for its roughly 47,000 seasonal employees was around $12 per hour. In mid-January VR offered a $2-an-hour bonus for employees who stay on until the end of the season.

In recent years, VR has set itself up for local disaster. The universal Epic Pass was a huge boon to average skiers, and a tonic to investors; it has transformed the resort industry with one simple, game-changing mantra: Skiing will now be purchased in advance. Meanwhile, VR took steps to bolster the bottom line for shareholders, such as slashing middle-management salaries by centralizing most corporate functions at its Broomfield, Colorado headquarters. The unintended consequence is a corporation slow to react to emerging local problems. Off-site marketing and finance personnel are blind to the nuances of local markets, and local issues. But the bridge too far was the cutback in local human-resources personnel, and the consequent loss of on-site expertise in local recruiting tactics, transportation and housing issues. Payroll functions were moved to an app that didn’t work.

As part of VR’s campaign to maximize margin in every segment, it built retail, lodging, food service and transportation enterprises that compete with local businesses. Building employee housing is always difficult, but alienating prominent locals doesn’t help.

VR cut the price by 20 percent and sold more than 2.1 million Epic Passes last summer, up 76 percent from pre-Covid 2019. According to its December 9 quarterly report, the company sailed into the season holding $1.5 billion in cash. It can well afford to spend what’s needed to fix local problems. Those problems now include settling class-action lawsuits by employees, meeting obligations under new collective bargaining agreements—and fixing housing and transportation issues. While they’re at it, they need affordable learn-to-ski packages for first-timers who get the itch in January, and improved access to free or cheap parking.

The original Vail Associates, from opening day in 1962, set the gold standard for American skiing. Vail offered the best slope grooming in the world. It recruited a top-ranked ski school. Vail’s managers, many of them veterans of the 10th Mountain Division, promoted skiing culture, for example by enlisting well-known skiers like Pepi Gramshammer and Dave and Renie Gorsuch to establish businesses in town, and later, under George Gillett, by bringing the World Championships to town. When the private equity firm Apollo Partners took VR public in 1997, they did what Wall Street always does: managed for shareholder value rather than customer and employee morale. To skiers, it now looks like VR has been cannibalizing VA’s good will.

According to annual reports, in fiscal year 2019 (the last pre-Covid year), VR’s mountain-operations revenue was $1.9 billion, and company-wide gross profit margin (EBITDA) was 36 percent. The National Ski Areas Association Economic Analysis shows the average large North American ski resort EBITDA then at about 26 percent. The difference was not only Vail’s success in selling season passes, but in strict cost control. To solve the employee crunch and relieve skier crowding, VR may have to give back some of that margin. With its 25 percent market share (in skier visits), the sport needs VR to succeed.

Will spending that money affect the stock price? Some 95 percent of VR stock is held by institutional investors, who may not care much about employee and skier morale. Closely held resorts have more freedom of action, and they’ve shown it this season to the benefit of their guests, employees and the communities they operate in. The other major resort conglomerate, Alterra of the Ikon Pass, has from day one taken the decentralized path, ceding control to its individual resorts. Aspen in mid-February gave a $3-an-hour raise to every employee in the company.

Rob Katz, the change-agent who created both the Epic Pass and VR’s 44-resort empire, stepped down as CEO in the fall and is now executive chairman of the board. His handpicked successor, veteran Kirsten Lynch, the data-driven marketer who has brainstormed the Epic Pass metrics, is now in the hot seat. “One of the hallmarks of our company is agility and change,” Lynch told the Wall Street Journal in its January 15 story “Steep Slope for a Ski Empire.” By the time you read this, in March, we’ll have seen how agile VR can be.

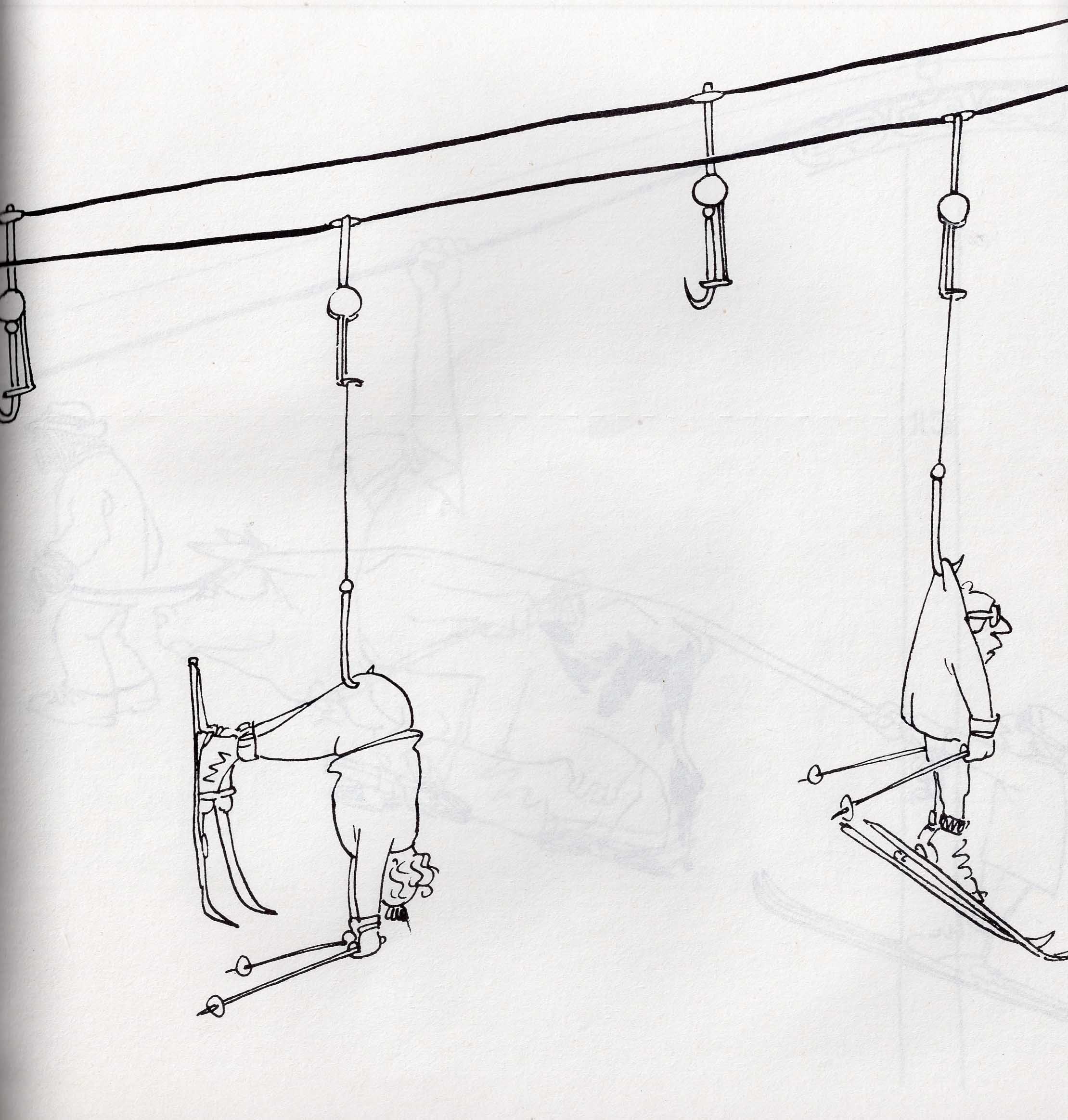

Image at top of page: Skiers on the hook, by Rudiger Fahrner

Table of Contents

WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP ($3,000+)

BerkshireEast/Catamount Mountain Resorts

Gorsuch

Warren and Laurie Miller

Sport Obermeyer

Polartec

CHAMPIONSHIP ($2,000)

Fairbank Group: Bromley, Cranmore, Jiminy Peak

Hickory & Tweed

Rossignol

Snowsports Merchandising Corporation

WORLD CUP ($1,000)

Aspen Skiing Company

Bogner of America

Boyne Resorts

Dale of Norway

Darn Tough Vermont

Dynastar/Lange/Look

Gordini USA Inc/Kombi LTD

Head Wintersports

Intuition Sports

Mammoth Mountain

Marker/Völkl USA

National Ski Areas Association

North Carolina Ski Areas Association

Outdoor Retailer

Ski Area Management

Ski Country Sports

Sports Specialists Ltd

Sugar Mountain

Sun Valley Resort

Vintage Ski World

World Cup Supply

GOLD MEDAL ($700)

Larson's Ski & Sports

Race Place/Beast Tuning Tools

The Ski Company (Rochester NY)

Thule

SILVER MEDAL ($500)

Alta Ski Area

Boden Architecture PLLC

Dalbello Sports

Deer Valley

EcoSign Mountain Resort Planners

Elan

Fera International

Holiday Valley Resort

Hotronic USA/Wintersteiger

Leki

Masterfit Enterprises

McWhorter Driscoll LLC

Metropolitan New York Ski Council

Mt. Bachelor

New Jersey Ski & Snowboard Council

Nils

Russell Mace Vacation Homes

SchoellerTextil

Scott Sports

Seirus Innovations

SeniorsSkiing.com

Ski Utah

Steamboat Ski & Resort Corp

Sundance Mountain Resort

Swiss Academic Ski Club

Tecnica Group USA

Timberline Lodge and Ski Area

Trapp Family Lodge

Western Winter Sports Reps Association

World Pro Ski Tour

Yellowstone Club