SKIING HISTORY

Editor Seth Masia

Managing Editor Greg Ditrinco

Consulting Editor Cindy Hirschfeld

Art Director Edna Baker

Editorial Board

Seth Masia, Chairman

John Allen, Andy Bigford, John Caldwell, Jeremy Davis, Kirby Gilbert, Paul Hooge, Jeff Leich, Bob Soden, Ingrid Wicken

Founding Editors

Morten Lund, Glenn Parkinson

To preserve skiing history and to increase awareness of the sport’s heritage

ISHA Founder

Mason Beekley, 1927–2001

ISHA Board of Directors

Rick Moulton, Chairman

Seth Masia, President

Wini Jones, Vice President

Jeff Blumenfeld, Vice President

John McMurtry, Vice President

Bob Soden (Canada), Treasurer

Einar Sunde, Secretary

Richard Allen, Skip Beitzel, Michael Calderone, Dick Cutler, Ken Hugessen (Canada), David Ingemie, Joe Jay Jalbert, Henri Rivers, Charles Sanders, Christof Thöny (Austria), Ivan Wagner (Switzerland)

Presidential Circle

Christin Cooper, Billy Kidd, Jean-Claude Killy, Bode Miller, Doug Pfeiffer, Penny Pitou, Nancy Greene Raine

Executive Director

Janet White

janet@skiinghistory.org

Membership Services

Laurie Glover

(802) 375-1105

laurie@skiinghistory.org

Corporate Sponsorships

Peter Kirkpatrick

(541) 944-3095

peterk10950@gmail.com

Bimonthly journal and official publication of the International Skiing History Association (ISHA)

Partners: U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame | Canadian Ski Museum and Hall of Fame

Alf Engen Ski Museum | North American Snowsports Journalists Association | Swiss Academic Ski Club

Skiing History (USPS No. 16-201, ISSN: 23293659) is published bimonthly by the International Skiing History Association, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255.

Periodicals postage paid at Manchester Center, VT and at additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send address changes to ISHA, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255

ISHA is a 501(c)(3) public charity. EIN: 06-1347398

Written permission from the editor is required to reproduce, in any manner, the contents of Skiing History, either in full or in part.

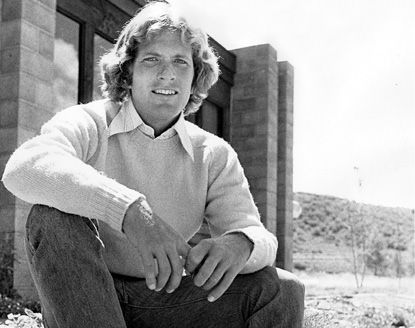

The Legacy of Spider Sabich

Belatedly elected to the Hall of Fame, the charismatic skier drove the professionalization of Alpine ski racing.

From the moment he entered the world on January 10, 1945, a ball of energy and gangly limbs, Vladimir Peter Sabich Jr. would be known as Spider. His father, Vlad, a World War II B-25 bomber pilot and California Highway Patrol officer, and his mother, Frances, the local postmistress, were hard-working and pragmatic. They raised their kids in Kyburz, California, nestled along the South Fork of the American River, where the Sierra Nevada foothills rise into the mountains enclosing Lake Tahoe.

Photo top of page: Spider Sabich in peak form at the Aspen World Cup slalom, 1968. Courtesy John Russell.

Hornets ski team.

Nature served up hunting and fishing in the summer and skiing in the winter. Spider, his older sister Mary and younger brother Steve (known to all as “Pinky”) learned to ski fast as part of Edelweiss Ski Area’s Red Hornets. Dede Brinkman, Spider’s Hornet teammate and lifelong friend, remembers the boy with big ears and a crooked front tooth as determined, focused and kind. By their teens, she says, “he had an aura. There was something magical about him.”

As the team packed into station wagons and racked up trophies throughout California, word of the “Highway 50 Boys” traveled beyond the Sierra. Spider and Pinky caught the attention of Bob Beattie, who offered them skiing scholarships at the University of Colorado. In 1963 Spider arrived in Boulder to study aeronautical engineering and ski. At the time, before the U.S. Ski Team was formed, Beattie’s CU Buffs were the de facto U.S. Men’s Ski Team. Spider and Pinky joined future Olympians Billy Kidd, Moose Barrows, Jimmie Heuga and Jere Elliot.

competition finish at a World Cup, 1969.

Beattie brought a hard-nosed, football-coach mentality to the ski team, implementing tough dryland training regimens. Bars were off limits. Instead, the team’s house, complete with swimming pool, became the party, where bands played, beer flowed and teammates bonded for life. Part drill sergeant, part cheerleader, part father, Beattie developed protective relationships with his athletes, no more than with Spider.

World Cup Victory at Heavenly

Over the course of his early career, Spider suffered seven broken legs. But by the spring of 1967, at age 22, he was whole and strong. He made his World Cup debut in the final slalom of the inaugural World Cup season at Jackson Hole, Wyoming, and finished sixth. The following year, he tackled the circuit full time. Teammates remember him for his street sense and maturity, as well as a penchant for fun and mischief.

In medal position after the first run of the 1968 Olympic slalom, Spider ended up fifth. The result matched Kidd’s GS finish as the best American skiing performance at the Games, and—though eclipsed by Jean-Claude Killy’s three gold medals—it heralded a bright future for American skiing.

During the 1968 season, Robert Redford was in Kitzbühel, Austria, researching his role for the 1969 film Downhill Racer. Though the original script based the lead on Olympic medalist Kidd, Redford gravitated to an unheralded, unpretentious and supremely charismatic teammate. “Spider Sabich was largely the inspiration for Dave Chappellet, probably more than any other one athlete,” says Redford. “What I remember most about Spider, and what I wanted to depict, was the way he attacked the race course, which to me reflected a feeling of going for broke.”

John Russell.

Spider ended his first full season on the World Cup with a win at Heavenly Valley, 30 miles from Kyburz. A crowd of 5,000 people lined the slope to cheer the hometown hero, who secured the win on a come-from-behind second run. Killy, who finished seventh in that race, won his second overall World Cup title and then retired.

Over the next two seasons on the World Cup, Spider won three more podiums and 11 top-10 results for a career total of 16 finishes in the top 10. Meanwhile, Beattie had moved on to launch the World Pro Skiing Tour (WPS), with Kidd as its star. After winning the FIS World Combined Championship in 1970, Kidd immediately turned pro and won the 1970 WPS championship as well. Spider, who was still competing on the World Cup, grew increasingly restless and unsettled at the hand-to-mouth existence it offered American skiers, while their European counterparts profited richly from sponsors. He finished out the 1970 season and went to Europe with the team the following winter, but his heart wasn’t in it.

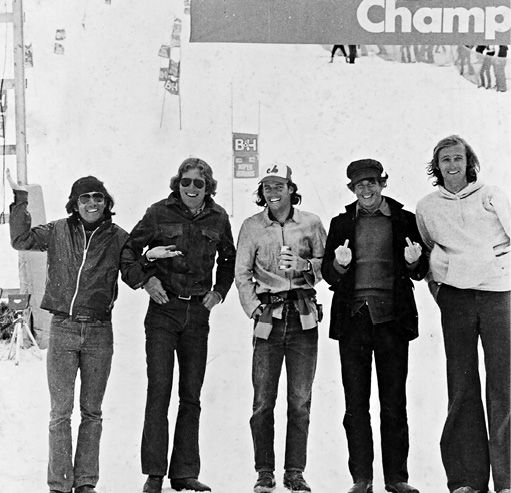

and Terry Palmer and Harald Stuefer

chillin' at Aspen Highlands, 1973.

Courtesy Norm Clasen.

Peter Miller, who chronicled the 1970–71 World Cup season in his book The 30,000 Mile Ski Race, summed up the particular challenge for U.S. skiers: “The American racer is a lonely figure on the international circuit. He is an amateur competing against professionals.” Miller also captured the personality conflicts within the team, under the disciplined coaching of Willy Schaeffler. None of it meshed with Spider’s motivations or personality, and he was ripe for change.

To Tyler Palmer, a 20-year-old slalom phenom on the World Cup during the 1970-71 season, Spider was both mentor and friend. In early January, the night before the slalom race in Berchtesgaden, Spider told Palmer he’d be leaving to join Beattie’s WPS. “My stomach hit the floor,” remembers Palmer. “You’re going to be fine,” Spider assured Palmer. “You’ve got everything I’ve got. Don’t hold back.” The next day Palmer, starting 61st, finished fourth. Two weeks later he scored his first World Cup victory.

Spider flew home immediately after Berchtesgaden. “It was such a relief to stop racing as an amateur,” Spider told Sports Illustrated in 1971. “I was fed up with the hypocrisy. Fed up with racing against guys who were making $50,000 a year, guys who had other people to wax their skis, sharpen their edges and who could go home when they got tired. I was nervous trying to compete with what I thought were insufficient weapons. Now I have no worries.”

Going Pro

Spider won his first pro race on February 4, 1971, at Hunter Mountain, New York, pocketing a check for $1,250. “The next thing we know, we’re getting reports Spider is winning every race.” recalls Hank Kashiwa, a U.S. Ski Team racer who joined the WPS in 1972. Spider went on to win seven races, beating Kidd in the final to win the overall tour title and $21,188. In the 1972 season Spider defended his title with nine more wins and broke his own record for prize money, making more than $50,000 ($360,000 today). That same year, the male U.S. Ski Team athletes were reimbursed $200 each for their commitment, the women $80.

Beattie. Courtesy John Russell

WPS brought the relatively unknown sport of ski racing to the American people in an easily understood format and in easily accessible venues—from high-profile Colorado’s Aspen and Vail to tiny Buck Hill, Minnesota, and Beech Mountain, North Carolina. In Beattie’s head-to-head, gladiatorial format, the rules were simple: cross the finish line first and you win. The tour brought the drama, excitement and fun of ski racing up close to viewers and offered them ready access to the athletes and their personalities.

The tour also allowed sponsors and athletes alike to connect with the audience while enabling athletes to maintain their independence and claim cold hard cash. Under amateur rules, U.S. Ski Team members could not directly work with sponsors, but on the pro circuit, skiers could serve as billboards, eager to sell their sponsors’ brands while creating their own. Explains John Demetre, whose sweater designs, especially one based on Spider’s Kyburz High School football jersey, exploded in popularity, “This was showing America Demetre every weekend.”

point to connect with young fans.

Courtesy John Russell

Regular TV coverage on ABC and NBC, as well as Beattie’s made-for-TV celebrity pro-ams, ensured attention, sponsors and prize money for WPS. In its first season, prize money totaled $92,500. Over the next four years, the amount had grown to more than $500,000. Spider’s laid-back attitude, approachable personality and contagious joie de vivre made him a marketer’s dream, and he earned more than $150,000 annually from sponsors. Said Gordi Eaton, then racing director at K2, “Having Spider ... you knew he was going to handle the public side of the thing well because he loved people and could sell anything to anyone.”

In tirelessly promoting the tour, Spider took his sponsors along for the ride, none more so than K2. At home, he charmed the brand’s factory workers, retailers and customers, and diligently worked trade shows and press conferences to win the hearts and attention of fans. In Europe, where the American ski companies had previously garnered little credibility, he represented the free-spirited ambition and legitimacy of American skiing, and skis.

Klaus Obermeyer once described Spider as “a man drinking life out of a full cup.” Spider could seamlessly switch from being laser focused on course to being friendly elsewhere, headlining everything from autograph sessions to wet T-shirt contests and sponsor parties. He’d pound a glass of water before bedtime, then be first up in the morning to train. The ambassador of hard work and fun was eminently approachable, especially around kids, for whom he’d get down on his knee to have eye contact while signing autographs.

Explained the late Gaylord Guenin, the WPS PR director, “It was simply Sabich being Sabich. . . . He brought an honest vitality to the sport that can be compared to the vitality Joe Namath brought to football.”

Meanwhile, the restrictions on amateur skiers tightened further, climaxing with the disqualification of Austria’s top skier, Karl Schranz, from the 1972 Sapporo Olympics for “professionalism.” This impelled more top Olympians, enticed by Spider’s success and lifestyle, to travel directly from the Games to join the WPS. Among them were Kashiwa and Palmer. As more World Cup racers joined the ranks and learned the format, Spider rolled on to defend his title and lead ski racing’s revolution.

A Plane, a Porsche and a Pad

Spider embodied everything that Beattie had imagined WPS could provide: American ski racers making a living on their own terms, on their own turf, and using it as a springboard to their professional lives. With his earnings and competing near home, Spider was able to enjoy a lifestyle similar to that of European ski stars. He engineered a home in Aspen’s Starwood neighborhood, near his friend John Denver. The house was neither huge nor showy, but a unique creation featuring California timber, curved stone walls and a waterbed in the living room. He earned his pilot’s license and bought a twin-engine Piper Aztec that he often flew to competitions.

Aspen. Aspen Historical Society, Aspen

Times Collection

“He had the plane, the nice house, the Porsche. We wanted to be like him,” says fellow pro Dan Mooney, while noting that no competitors begrudged Spider his success. They fully understood the work it took and his talent for walking the line between fierce competitor and life of the party. Spider generously mentored incoming athletes, teaching them that making it as a pro meant managing training, travel, equipment, sponsors and one’s own competitive instincts. It meant working hard in the gym and on the hill, in the ski room and the board room, at trade shows, in ski shops and, most importantly, with sponsors.

Whereas amateurs were punished for promoting sponsors, pros were fined for not going to sponsor parties. Terry Palmer recalls Spider teaching him how to drink at tour parties by having one shot, then discreetly throwing subsequent drinks over his shoulder. His message, Palmer recalls, was always clear: “If you’re going to be good, if you’re going to make money at this, if we’re going to have a good tour, you’re going to have to work hard.”

Sponsors and athletes organized themselves into factory teams, bringing together the financial and logistical support of a national team while preserving the monetary incentive for individual success. So compelling was the tour that Killy came out of retirement for the 1972–73 season and joinedWPS, bringing it international attention.

Kashiwa was with Spider when they learned Killy was joining the tour and felt his demeanor change. “I think he wanted to prove that we [on the WPS] were the best skiers in the world,” says Kashiwa. Initially unprepared for the physical challenge of the format, Killy earned $225 total in his first race but retrenched over the Christmas break and roared back, winning five races to Spider’s three. Spider and Killy’s epic battle for the 1973 season title—recounted in the film Spider and the Frenchman and in Killy’s book Comeback—ended when Spider crashed off a bump, badly injuring his neck and shoulder.

Despite losing the title to Killy, and amid the infusion of new stars, Spider graced the cover of GQ magazine in November 1974. Clutching his red, white and blue K2 skis, in his signature Demetre sweater, he remained the face of the American pro tour and the picture of success. As tour director Nappy Neaman once put it, “Every kid wanted to be Spider. Every girl wanted to date Spider.”

As a brand ambassador for Snowmass (the resort’s only front man since Stein Eriksen), Spider deftly navigated all aspects of Aspen’s scene, comfortably mingling with cowboys, ski bums, celebrities and the ultra-rich. In 1972, at a pro-am event in California, he met French singer Claudine Longet. Recently and amicably divorced from Andy Williams, who had facilitated her Hollywood career, Longet and her three children later moved in with Spider. For a time, the couple seemed genuinely in love, but friends recall that her quick temper and possessiveness turned the intensity of the relationship into a liability. This shift coincided with Spider’s competitive decline. “If you’re out of shape by the eighth run, you’re not going to be able to do the things that you’re telling yourself mentally you can do,” he said. “And that breeds inconsistency. And in this game, inconsistency is elimination.”

Last Runs

In 1974, Spider managed two wins and limped through the season to finish fifth in the tour standings. By then his litany of injuries included knee, back and neck problems—on top of the seven early-career broken legs. Publicly he made no excuses, remaining upbeat and optimistic about the future. After missing the entire 1975 season due to injury, Spider knew his ski racing career was coming to its natural end. He and Beattie (as friend and advisor) together plotted the next step, which would likely involve K2 and Snowmass, and possibly ski area development, real estate and TV commentary. With Spider’s talent, education and connections, his next chapter promised to be as exciting as the last, and less stressful.

By March 1976, having qualified for the weekend round of 32 only twice that season, Spider decided to quit two things that were no longer healthy for him: ski racing and Claudine. He told Tyler Palmer as much in their hotel room in Collingwood, Ontario, before the penultimate race of the season. Palmer, upset at the prospect of once again losing his teammate and mentor, also mistrusted Longet. “I told him ‘Just be careful with her,’” Palmer recalls. “That was the last I saw of him.”

Longet and her kids were to move out by April 1. On March 21, Sabich spent his afternoon training at Buttermilk, while Longet, according to toxicology reports that were ultimately disallowed as evidence, spent hers indulging in Aspen’s notorious après ski. After a short visit with Beattie, Spider headed home to change. He planned to meet Beattie later that evening and to fly to the annual ski trade show in Vegas the next day. Instead, Longet shot him to death in his own bathroom, with the gun his dad had bought as a souvenir from the ’68 Olympics. Spider was 31 years old.

While the shooting itself still holds mysteries, the aftermath of the killing, the trial and the events that led to Longet’s sentence—a $250 fine and 30 days at the Pitkin County Jail to be served at a time of her choosing—are well chronicled (see “Spider Sabich: A Tale Larger Than Life,” by Charlie Meyers, in Skiing Heritage, September 2006).

A Long Legacy

Under Chuck Ferries’ supervision, K2 had introduced its first race ski in 1969. Spider’s success helped bring the brand to prominence, and by 1975 it had achieved a 30 percent market share in North America. Iconic, fiercely independent stars like Phil and Steve Mahre, Glen Plake and Bode Miller continued to build the uniquely American brand. Beattie’s WPS thrived, and the popularity of the format inspired a women’s pro tour, started by Jill Wing Heck in 1978. In 1993, Bernhard Knauss became the first pro skier to break the $1 million mark in tour winnings. “Even in the 90s, this name Spider Sabich meant something,” says Knauss. “I realized from the beginning that if I work hard enough and do well it can change my life.”

Dede Brinkman. Courtesy Dede

Brinkman.

Skier Erik Schlopy revived his own amateur career with the technique and independence he learned through the pro format. When it came to naming his own son, Schlopy was inspired by one person: “Spider Sabich was the coolest racer of all time,” he says. Young Spider Schlopy now races for the Park City ski team. Today, a revived pro tour features both amateur and pro skiers facing off with no eligibility restrictions, and its star, Rob Cone, is a laid-back former U.S. Ski Teamer and collegiate skier who races on his own terms. Meanwhile, at the Spider Sabich Race Arena in Snowmass, people of all ages come to experience the rush of head-to-head racing.

Spider lives on in a more tangible way, too. “In the early summer of 1967,” Dede Brinkman recounts, “he and I spent the night together, and we conceived a child.” At the time, both were otherwise engaged, Dede to her future husband and Spider with his skiing career. The two decided to keep this secret. Dede remained close with Spider, as their lives took both of them from Tahoe to Boulder and, eventually, to Aspen. After her divorce, she lived in Starwood, where their daughter, Missy, had a close connection to Spider.

When Brinkman told her daughter, then age 20, the truth, “there was a lot more about my life that made sense,” says Missy. She now runs a successful coffee business in Salt Lake City, and her own daughter, Grace, recently graduated from UC Berkeley. They share a love of skiing and an appreciation for Spider’s ideals, which Missy describes as “doing what’s right, not what is easy. And making a difference.” While Spider never met his own grandchild, his parents did. Missy recalls Frances Sabich’s words: “It’s just the nicest thing to know there’s a legacy.’”

Regular contributor Edith Thys Morgan spent nine years on the U.S. Ski Team, competing in three World Championships and two Olympics. She last wrote about “What to Expect When You’re Inspecting” in the January-February 2022 issue.

Spider Lives: On Film and in the Hall of Fame

Spider Sabich’s life is commemorated in the new film Spider Lives, which will hold its premiere at 5:30 pm on March 25 during Skiing History Week in Sun Valley. Produced by Christin Cooper, Mike Hundert, Mark Taché, Edith Thys Morgan and Hayden Scott, the 90-minute film earned a 2021 ISHA Film Award. On March 26, Sabich will be inducted into the U.S. Ski & Snowboard Hall of Fame, during its banquet in Sun Valley.

Table of Contents

WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP ($3,000+)

BerkshireEast/Catamount Mountain Resorts

Gorsuch

Warren and Laurie Miller

Sport Obermeyer

Polartec

CHAMPIONSHIP ($2,000)

Fairbank Group: Bromley, Cranmore, Jiminy Peak

Hickory & Tweed

Rossignol

Snowsports Merchandising Corporation

WORLD CUP ($1,000)

Aspen Skiing Company

Bogner of America

Boyne Resorts

Dale of Norway

Darn Tough Vermont

Dynastar/Lange/Look

Gordini USA Inc/Kombi LTD

Head Wintersports

Intuition Sports

Mammoth Mountain

Marker/Völkl USA

National Ski Areas Association

North Carolina Ski Areas Association

Outdoor Retailer

Ski Area Management

Ski Country Sports

Sports Specialists Ltd

Sugar Mountain

Sun Valley Resort

Vintage Ski World

World Cup Supply

GOLD MEDAL ($700)

Larson's Ski & Sports

Race Place/Beast Tuning Tools

The Ski Company (Rochester NY)

Thule

SILVER MEDAL ($500)

Alta Ski Area

Boden Architecture PLLC

Dalbello Sports

Deer Valley

EcoSign Mountain Resort Planners

Elan

Fera International

Holiday Valley Resort

Hotronic USA/Wintersteiger

Leki

Masterfit Enterprises

McWhorter Driscoll LLC

Metropolitan New York Ski Council

Mt. Bachelor

New Jersey Ski & Snowboard Council

Nils

Russell Mace Vacation Homes

SchoellerTextil

Scott Sports

Seirus Innovations

SeniorsSkiing.com

Ski Utah

Steamboat Ski & Resort Corp

Sundance Mountain Resort

Swiss Academic Ski Club

Tecnica Group USA

Timberline Lodge and Ski Area

Trapp Family Lodge

Western Winter Sports Reps Association

World Pro Ski Tour

Yellowstone Club